The Market Standoff

By dawn the storm had burned itself out. The forest was dripping and clean, all the violence of the night washed into silence. Mist curled low over the ground, thin as smoke, and the air carried that raw, sharp smell of new rain, moss, soil, bark, the scent of things that had survived.

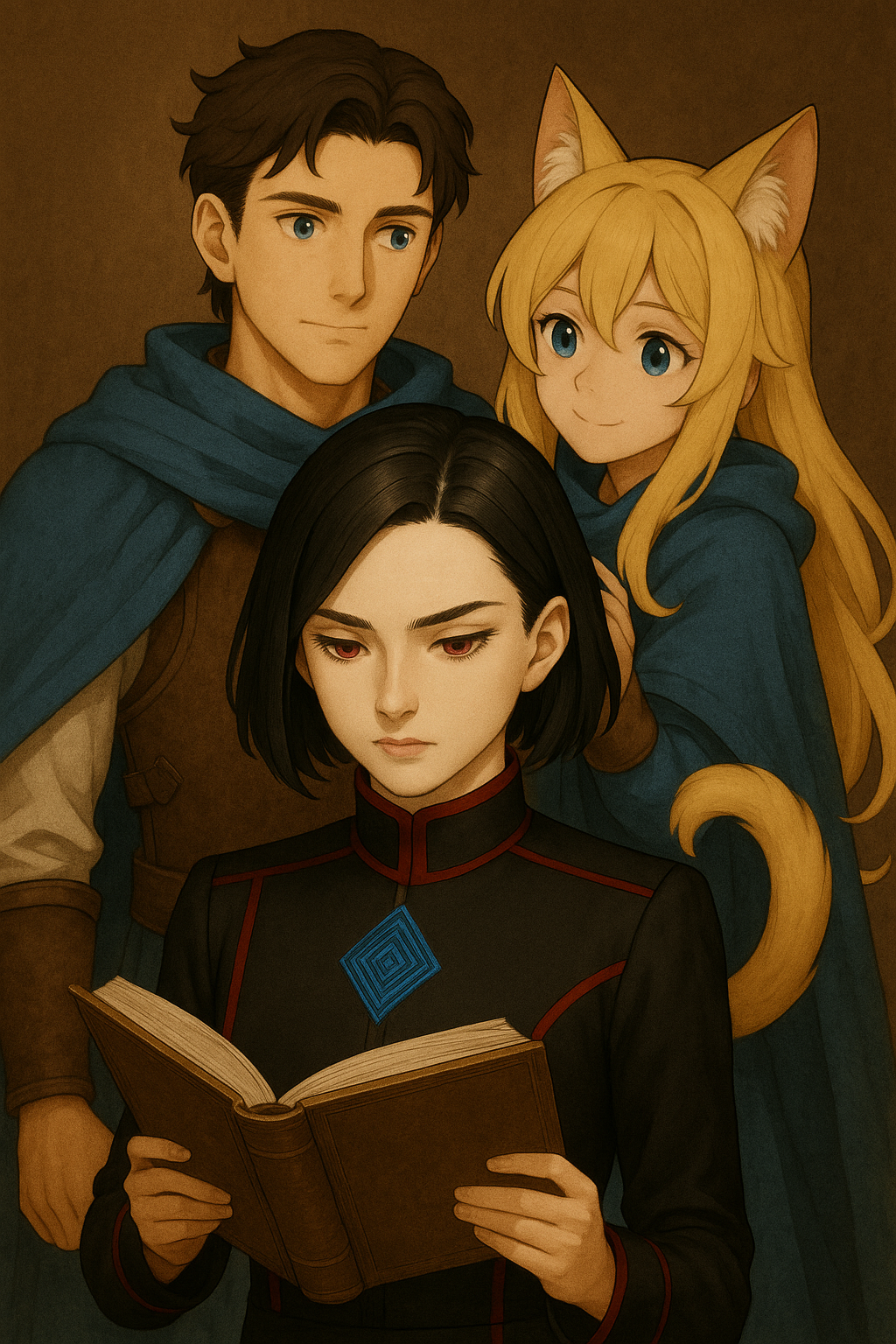

I was the first to stir. The stink, the humiliation of it, was gone. My fur had dried into something soft again, smooth under my fingers. The air didn’t burn my pride anymore; it tasted like relief, like rebirth. I stretched, long and lazy, spine arcing, tail swishing against the damp earth as I breathed in the clean morning. A low hum slipped from my throat, not a purr, not yet, but something close.

Master was still asleep, or pretending, more likely. He always half-watched the world even with his eyes closed, the way soldiers do when they’ve seen too many mornings they didn’t earn. The lamp had guttered out sometime before dawn, leaving his face cut in half by the pale grey light leaking through the seams of the tent.

I crouched beside him, grinning to myself. “Master,” I said quietly, leaning close, voice syrup-thick with mischief. “Wake up. The world’s still here. Somehow.”

He blinked once, slow, then opened his eyes, and that was all, no startle, no groggy confusion, just that same quiet clarity, the kind that makes you wonder if he ever truly sleeps. He sat up with the weary grace of someone who’s already lived the day ahead in his head.

He didn’t speak at first, just reached for the pack at his side, pulled out a strip of dried venison, tore it in half, and passed me a piece. I took it between my teeth, still crouched, tail flicking idly.

“If you’ve got so much energy this morning,” he said finally, voice rough with sleep but edged in that dry, noir amusement that always cuts through the air like smoke curling off a match, “you can help put the tent down.”

There it was, that tone that lived somewhere between command and challenge. He said it like a man lighting a smoke on a battlefield; calm, dry, unimpressed by the apocalypse.

I laughed, low and bright, the sound curling through the morning fog. “That’s it? No ‘good morning, Aliza’? No poetic praise for the miracle of my scentless resurrection?” My grin widened. “You wound me, Master.”

He looked up at me, one eyebrow raised, eyes half-shadowed by the light. “You’ll survive,” he said simply, tearing another bite from the jerky.

My tail flicked again, a restless, happy rhythm, before I dropped onto my hands and knees beside him and began tugging at the tent stakes with a kind of feral enthusiasm. The iron tips came free one by one, wet soil clinging to my fingers. “You know,” I said, glancing over my shoulder, “you could say you missed the smell. Just a little.”

He gave a quiet, disbelieving exhale ,almost a laugh, if you listened close enough, and started folding the leather panels with that same unhurried precision. The mist thickened around us, the last of the rain dripping from the canopy overhead. The forest was silent but alive, birds calling far off, the soft patter of droplets falling from leaves, the crackle of something small scurrying through wet underbrush.

I packed in rhythm with him, humming softly under my breath, every motion carrying that strange, feline satisfaction that only comes after chaos, the thrill of having outlasted something. My tail brushed his arm once, twice, a quiet touch, deliberate, possessive.

“You really don’t know how lucky you are,” I said, voice lighter now. “Most people don’t get to wake up next to a miracle twice.”

He didn’t look up, didn’t take the bait. “You’re not a miracle,” he said.

That made me laugh properly, the sound spilling out into the clean air. “You say that like it’s a bad thing.”

The tent was down by the time the sun finally burned through the mist, turning the dew on the leaves into points of light. The forest steamed faintly, gold and green, alive again. I slung the packed canvas over my shoulder and looked toward the distant line of Mire Point’s towers cutting through the haze.

By late morning the clouds had thinned to pale streaks, the world scrubbed clean by the night’s downpour. Our boots sank deep into the soft road, clay and rain making each step a slow drag through the waking marshland. Mire Point’s silhouette began to form ahead of us, the sandstone curve of its walls rising like a half-buried memory from the bog.

The land here always smelled of something alive and rotting at once. Cabbage fields unfurled along the outer ditches, their waxy leaves slick with rain. Goblin farmers worked them in silence, bent and patient, mud up to their knees. The air had that faint sting of compost and smoke, the scent of the bog reclaiming everything that didn’t fight back.

The first checkpoint stood just before the old quarry line, a narrow cut of road that climbed toward the heart of the keep. They’d built an “airlock” there, two gates, an outer and inner, with the slope between them reinforced by packed stone. A raised motte sat above it, its crown bristling with timber palisades. From there a tower watched the crossroads, a square-toothed silhouette against the pale sky.

I could see movement up there, guards changing shifts, smoke from a brazier curling through the chill air. The clang of a hammer drifted down from the barracks perched just behind the wall, the rhythm of repair and routine. The sound always echoed in Mire Point, like the city itself was a forge that never cooled.

We passed beneath the outer gate. The guards glanced down, saw Master’s cloak, and didn’t bother with questions. Respect and fear often looked the same here.

Past the second gate, the road levelled into the Cat Tail District. The ground was still damp, the puddles catching pieces of sunlight and reflecting the soft brown glow of sandstone walls. Wooden catwalks and narrow bridges crisscrossed the lanes, leading between clusters of low stone compounds. Goblin families had built them in tight circles, each cluster with a banner above its entryway, crude symbols daubed in tar, clan marks, warnings, pride.

The compounds themselves looked alive: smoke curling from small chimneys, the sound of water sloshing as buckets were dragged from gutters, and the occasional burst of laughter that carried through the alleys. Compound heads stood at doorways, watching us as we passed, some with respect, others with that wary unease that never quite faded around outsiders, even ones they owed.

Between the compounds, the occasional freestanding house broke the pattern, newer structures, Alderian-built. You could tell by the cut of the stone and the symmetry of the windows. That’s where the non-goblins lived, traders, scribes, stray adventurers who’d settled here for coin or cause. Their doors were cleaner, their faces less so.

The further we went, the thicker the air became. The smell of bog rolled in from the south, heavy and wet, laced with the earthy sweetness of cat tail farms nearby. It clung to my fur, to my tongue, that distinct blend of mud, reed, and stagnant water that marked Mire Point as its own creature. I hated that smell and loved it too. It meant home. It meant we’d returned to something we’d made out of nothing, a fortress stitched together by mud, stone, and stubbornness.

The long market hit us before we even turned the corner, not just noise, but tension, thick and vibrating like the air before lightning. The street was slick from the rain, the cobbles dark and wet beneath a sky still heavy with cloud.

On one side stood the workers, maybe forty of them, goblins mostly, a few dwarfs and catgirls still wearing the rags of cattail mill uniforms. Their clothes were streaked with grease and cattail dust, and every single one of them looked tired in that hollow-eyed way that comes from hunger rather than fatigue. Some held tools, spindles, hammers, blades stripped from looms, nothing sharp enough to win, but enough to make a statement.

On the other side, the guards.

Ten catgirls in copper chainmail stood in a curved formation, armour dull but solid, shortbows slung across their backs, short swords drawn. The metal caught the faint light like burnished bronze. They looked disciplined, the kind of order that doesn’t come from loyalty but repetition. The only motion came from their tails, flicking in unison, a restless warning.

The moment we stepped closer, the smell hit, cattail fibre, damp copper, wet fur, and the sharp, bitter tang of cattail bread burned in the ovens nearby. The sort of scent that clung to a place like Mire Point and never washed away.

At the centre of it all stood her.

Lisette Ferrah, Cattail District header, The only non goblin header, copper-plate armour instead of chain, a barbute that framed her golden eyes. Her tail stood still, perfectly straight, command posture, except for the smallest twitch when she noticed us coming down the street.

Perception Check (Aliza): d20 (14) + 2 = 16

That one curl of her tail told me everything. A single flick, no wider than a breath, but it wasn’t the twitch of alertness. It was recognition. And interest.

I froze mid-step, pupils narrowing.

She’d looked at him.

Not in the formal sense, not the dutiful “yes, sir” way soldiers did, but the kind that makes my claws itch. I didn’t even think about it. My muscles were already coiled.

Agility Check (Aliza): d20 (18) + 4 = 22

I was a blur of motion, sliding past the edge of the milling crowd before anyone registered the movement. The splash of my boots against the wet cobbles cut the tension like a blade through silk.

In a heartbeat, I landed, not gracefully, but deliberately hard, right in front of her. The copper of her breastplate rattled as I hit the ground, tail lashing like a whip behind me. The guards jerked, startled, hands tightening on hilts, but Lisette didn’t move. Not yet.

The noise of the workers’ shouting dulled, like the whole market was holding its breath.

Her eyes locked on mine, sharp, trained, but she couldn’t hide that flicker of confusion.

I bared my teeth in a wild snarl, fangs baring as my tail whipped frenzied behind me.

Behind us, the workers were still yelling. The guards were shouting back, voices blending into a snarl of protest and command. A few of the goblins were pushing against the chain line, others trying to pull them back. One of the catgirl guards had her bow half-raised, eyes flicking between her commander and the crowd.

The sound of the market was chaos, not violence, not yet, but the sort of unstable equilibrium that could collapse with one wrong word. Overhead, the clouds hung heavy and low, turning the light to a dull bronze that caught on every weapon and every set of eyes.

“He’s mine,” I hissed, every syllable shaking with the heat under my skin. “MINE. Not your commander, not your fantasy, not something you get to look at.”

Her breath hitched. I leaned closer, until she could feel the tips of my fangs against her ear. “You want a Master?” I whispered, low, dangerous, sweet like poison. “Go dig one out of the gutter. You don’t touch mine. You don’t even think about mine.”

I pressed my hand harder against her chestplate, feeling the metal flex under the strain. “You see him again, and those pretty eyes of yours won’t see anything else.”

The bond pulsed, not angry, not commanding, just there, steady, like a hand on my shoulder. It didn’t calm me. It just anchored me long enough not to break her jaw.

My breathing came in fast, shallow bursts. My tail lashed once more, scattering rain from the stones. The whole street had gone dead quiet, every worker, every guard watching, frozen. The sound of the distant mills creaked somewhere beyond the fog, a hollow metallic sigh.

I smiled then, slow, too wide, and rose from her with a kind of deliberate grace, like a cat deciding not to kill the mouse after all. My voice, when it came, was all velvet and venom.

“Remember this,” I said, eyes still locked on hers. “You don’t look at him. You don’t exist near him unless I allow it.”

Then I turned, still smiling, tail curling lazily now, though the pulse in my throat hadn’t slowed. Every step back toward him felt like pulling breath again after drowning. The noise of the market returned slowly, cautious, as if the air itself was afraid to make sound until I was standing beside him again.

Master moved like the world was made of glass, unhurried, unbothered, stepping through the chaos I’d just torn open. The crowd parted for him instinctively; even the guards shifted back, unsure whether they’d just watched a breakdown or a declaration of law. He didn’t even glance at me as he knelt in the muck across from Lisette, who was still half on her back, armour splattered and eyes wide from the violence that had just passed over her.

His voice came out calm, too calm, that flat noir drawl he used when he was past anger and down in the quiet part of it. “What’s going on?” he asked.

It wasn’t a question that invited narrative; it was a question that dragged the truth out of your lungs. Lisette swallowed, breath still catching as she straightened. “The owner of the Cattail Mills, he hasn’t paid the workers, sir. One of the looms collapsed last week and shut the third mill down. They can’t work, and he refuses to issue rations until repairs are done.”

Master tilted his head just slightly, shadows cutting across his eyes. “So they haven’t eaten.”

She nodded, voice catching. “Two days.”

For a moment, he just looked at her, quiet and unreadable. Then he sighed softly, the sound colder than a blade. “Then kill him.”

Her ears twitched. “Sir?”

“Kill the owner,” he repeated, standing now, voice as smooth as rain on iron. “Slowly. Painfully. Privilege doesn’t make anyone untouchable. It makes them responsible.”

She hesitated, not in defiance, just shock, and looked to me, as if I might temper him. I didn’t. My eyes were still fixed on her throat, daring her to speak again.

Master turned away, ignoring both of us, his boots leaving dark prints in the wet stone as he faced the workers.

The shouting had died down; only a low murmur hung in the air, that wary sound of people who weren’t sure whether they’d just been saved or doomed. The workers stood in the open square between the mills, faces streaked with rain and cattail dust, children huddled at their legs.

When Master spoke, his voice cut through the drizzle like steel dragged across glass. “The mills will be repaired at top priority,” he said. “You’ll be paid for every day the looms are down.”

There was movement in the crowd, disbelief, cautious hope. A few of the goblins whispered among themselves, the word paid passing like a rumour.

He raised a hand, and silence fell. “Until the mills are working again, the keep will supply you with cattail bread, cabbage, dried meat and fish. Enough for you and your families.”

Someone, an older goblin with soot-black hands, called out, “And the owner?”

Master’s eyes lifted, a half-smile tugging at his mouth. “He’ll pay as well. One way or another.”

That shut everyone up.

His tone never rose, never carried the weight of command, but the air itself bent around it heavy, absolute. The guards shifted, tails twitching uneasily, and the workers bowed their heads like a tide rolling back from the shore.

Then he spoke again, quieter, darker. “The upper class thinks privilege is a crown,” he said. “It isn’t. It’s a debt. And when a man fails the people who built his comfort, he forfeits both.”

His eyes moved across the crowd, and for a heartbeat, I thought he was talking to more than just them. I thought maybe he was talking to Mire itself, to the bones of the city, to the ghosts that built it, to every lord and fool who’d mistaken fear for loyalty.

It happened in that flicker of silence after his voice left the air.

My claws were still pressed into the dirt where Lisette’s armour had been a second ago, her copper shell dented under my knees, my breath hot and ragged, tail twitching with all the leftover fury I hadn’t yet burned off. The world was still narrowed to her, her scent, her audacity, her mistake of existing in the same radius as him. The crowd had already begun to dissolve, voices soft as distant rain.

And then, he moved...

Five feet away before I noticed. Six.

My head turned, ears snapping to the sound of his boots on stone. Seven.

My pulse jumped.

Eight.

The air felt thinner.

Nine.

He didn’t look back. Not once. Just walking, calm as a man leaving a burning room, hands steady, coat brushing his legs, as if all this, me, the crowd, the chaos, was just another page to be turned.

Ten.

That’s when he stopped.

I blinked, breath catching mid-growl, claws flexing into the mud. The sudden space between us hit harder than any blow. Ten feet. The bond stretched, taut, trembling, that faint psychic thread pulling against my ribs. My tail froze. For a second, all the noise fell away again.

He turned, just slightly, not enough to face me. His voice carried like a line of cold steel through the drizzle.

“Are you coming or not?”

Every nerve in me jolted at once. The bond snapped back like a whip and I moved.

The crowd blurred, the rain vanished, the guards disappeared into streaks of copper and brown. My boots hit the ground in heavy, uneven beats as I barreled toward him. The distance collapsed in an instant.

And then I was there, crashing against him hard enough to make his balance falter. My arms locked around him, tail coiling tight around his waist, possessive, trembling, feral. My face pressed against the back of his cloak, the scent of iron and wet leather grounding me again.

“YOU DON'T JUST WALK AWAY,” I hissed into the fabric, the words half a snarl, half a plea. “NOT FROM ME, NOT EVER”

For a heartbeat, the world narrowed again. Just warmth and breath, the rain against our skin, the faint hum of the bond smoothing back into rhythm. My claws loosened, dragging softly down his arm.

He didn’t push me away. He never did. But he didn’t soften either.

“We have Pontune to deal with,” he said, voice level as if nothing had happened. “Or have you already forgotten about the hunters we found in the forest?”

The words cut sharper than reprimand. They anchored me.

My tail stilled, though it didn’t uncurl. I forced a breath through my teeth, laughter slipping out like a fractured sound, too light, too sweet. “Forgotten?” I murmured, leaning back enough to meet his eyes. “No, Master. I don’t forget. I remember EVERYTHING, always”

Behind us, the market went back to motion, guards dragging away the trembling mill owner, workers murmuring, Lisette still kneeling where I’d left her. But in that moment, none of it existed.

Only the two of us, rain falling through the gaps in the cat-tail roofs, my tail wound tight around him like a vow I didn’t need to speak.

TIGHTER AND TIGHTER

What a amzing story it is..

Thank, thank. Personally I think the POV is a bit much at times but I try to keep it inline with the charcter.

Yes but overall it was too good.. I would love to talk more about your story. Can we chat on any other platform? Cuz I am new to this platform and don't know much about this lol

I did start uploading on Royal Road as I started writing because of the 50k Nov challenge but then I'm new to that as well but you might not be :)

Ohh nice that you work hard for your story. Do you have discord where we can easily connect and talk more and easily?